SEATTLE’S FIRST WATCHMAKERS 1869 -1889

Bringing Time to the Public in the Pacific Northwest

By

Paul Middents FNAWCC

Standard time calibrated to the Greenwich meridian reached the nation

and the Pacific Northwest in 1884, about the same time a fifteen year

old German Jewish immigrant named Joseph Mayer arrived in Seattle and

took up the trade of watchmaker and jeweler. Eventually he became a

true clock maker specializing in street and tower clocks. His role in

spreading public time around the West over the next 50 years sparked my

interest in considering Seattle’s place in the jewelry and watchmaking

trade and its evolution while he was launching his career.

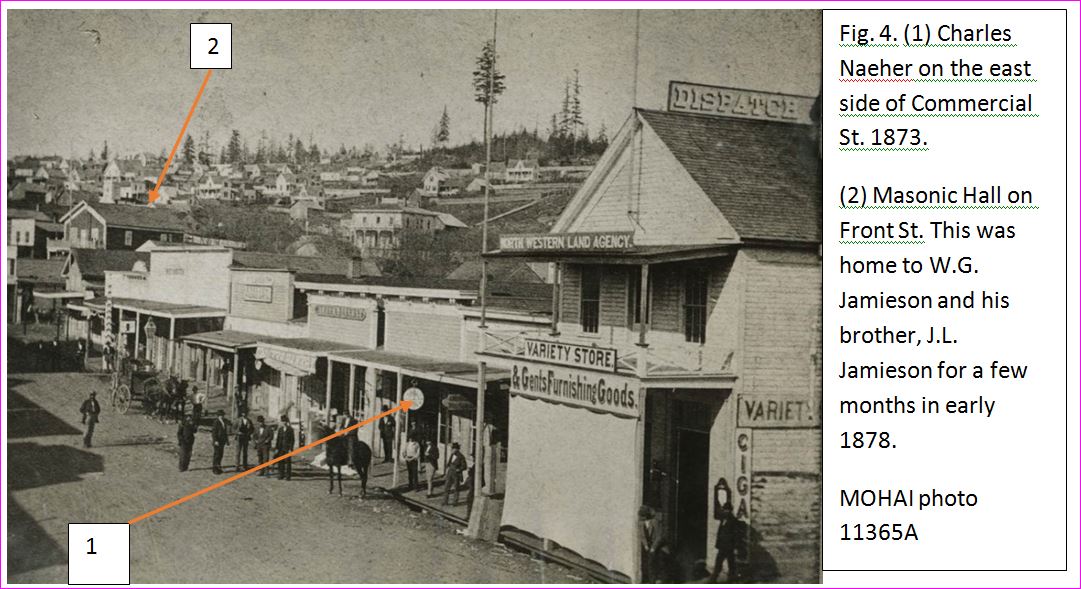

Fig.

1. This 1869 image

of Seattle shows a watchmaker’s sign on Commercial

St.—probably the first watchmaker in town. The sign was not a

functional timekeeper. (1) Seattle’s first watchmaker. East side of

Commercial St. between Main and Washington. (2) Masonic Hall on Front

St. This was home to W.G. Jamieson and his brother, J.L. Jamieson for a

few months in early 1878. From a panoramic Washington State Historical

Society photo (1991.1) of Seattle 1869 by Robinson.

First Watchmakers

A photo from 1865 of Commercial St. shows the buildings pictured in

Fig. 1 but the watchmaker’s sign is absent. , The territorial

capitol, Olympia, had one jeweler in 1861; Julien Guyot, a 35 year old

Swiss immigrant. A Pacific Coast Directory for 1867

lists three watchmakers in the Washington Territory; two east of the

Cascades in Walla Walla, then Washington Territory’s largest town

(population about 1400), and one in Port Townsend on the Olympic

Peninsula. Port Townsend was a contender for the territory’s

principal seaport and railway terminus. Seattle was a frontier village

with a population of 1107 in 1870, less than 20 years after its first

settlement by the Denny Party. By contrast, San Francisco, population

57,000, had 106 watchmakers and jewelers in 1860.

William G. Jamieson, a 25 year old immigrant from Victoria, Vancouver

Island, opened a jewelry business in September 1870. Fig. 2. An 1871

Pacific Coast Business Directory lists George W. Parker and Leonard P.

Smith as watchmakers and jewelers in Seattle. No addresses are

given. Smith, age 56, was born in Maine. He, together with his

wife and his 21 year son probably arrived before 1870 as did Parker.

Either

Fig. 2. (1) Jamieson’s first advertisement appearing in an 1870 issue

of the Olympia’s Washington Standard. (2), (3), (4) Advertisements from

the 1872 directory.

Parker or Smith could have occupied the location pictured above

in 1869. See also the 1878 map

Putting Seattle on the Map

Seattle literally was placed on the map in 1871 through the telegraphic

determination of the town’s longitude. The routine dissemination of

telegraphic standard time signals would not become available for almost

20 years. Each community ordered business according to local time which

was established by observing local noon which can be estimated by eye

or more precisely by an optical instrument such as a sextant or

transit. The arrival of railroads, scheduled steamer and ferry service

and telegraphic communication sparked public awareness of time and

brought the “public time era” to the Northwest. Men were carrying

watches in increasing numbers and the commercial life of cities and

towns was being conducted in accordance with the standard time for a

whole region. Jewelers were the first to provide reliable and accurate

local or standard time to the inhabitants of these towns.

Watchmakers could estimate local time but with an accurate longitude

they could make a precise determination of local time or time at any

other reference longitude through star observations. This was of

real significance to ship’s navigators in the harbor who were checking

their chronometers; to the watchmakers who were repairing and rating

chronometers; to railroad men and ferry boat men who were trying to

operate trains and ferries to a schedule. The watchmakers disseminated

time by regulators (precision pendulum clocks) or chronometers

displayed in their shops. They sold pocket watches emphasizing their

accurate timekeeping.

In August 1871 the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey established an

astronomical station consisting of a brick pier and temporary shelter

near Jackson and Front Streets about where Occidental Park is

now. The station was equipped with a meridian transit instrument

mounted on the brick pier. This was used for determining the latitude,

the local time and checking the rate of a chronometer via star

observations. Western Union provided a temporary telegraph connection

so time signals could be exchanged with a similar station on Washington

Square in San Francisco. The longitude of San Francisco had already

been determined by extensive astronomical observations. The longitude

difference between Seattle and San Francisco was determined by

exchanging telegraphic local time signals over an extended period.

Successful star observations and time signal exchanges were made on 12

nights. Forest fires throughout Oregon and the Washington

Territory caused frequent loss of telegraph connections. The San

Francisco observer in charge of the operation observed 602 transits of

81 stars on 38 nights.

Someone might have asked what the full extent of the country was

because the next Seattle longitude measurement determined the

difference between Seattle and Tatoosh Island. This was more likely

motivated by the need for an accurate position of the Cape Flattery

Lighthouse. The 1871 Jackson St. station had succumbed to urban

development by 1886. So in May 1886 USC&GS Assistant J.J. Gilbert

set up a new station on the grounds of the Washington Territorial

University consisting of a “suitable building and instrument pier” from

which the longitude difference of Tatoosh Island was determined.

Omaha marked the western extent of the national longitude net in 1884.

The net reached the far west and Washington Territory first in 1887

when Salt Lake City was connected to Walla Walla. In the summer of

1888, Edwin Smith, one of the Survey’s most noted Assistants found the

Seattle station established by Gilbert two years earlier, in good

condition. He described it as “on the grounds of the university at the

break of the hill sloping down to the art building”. A series of

exchanges that summer tied Seattle to the national longitude net via

Walla Walla and Portland. Thus the Washington Territorial

University (now the site of the Olympic Hotel) established the

longitude reference for the triangulation of western Washington

including our complex coastline and vital waterways.

Competing and Moving Around

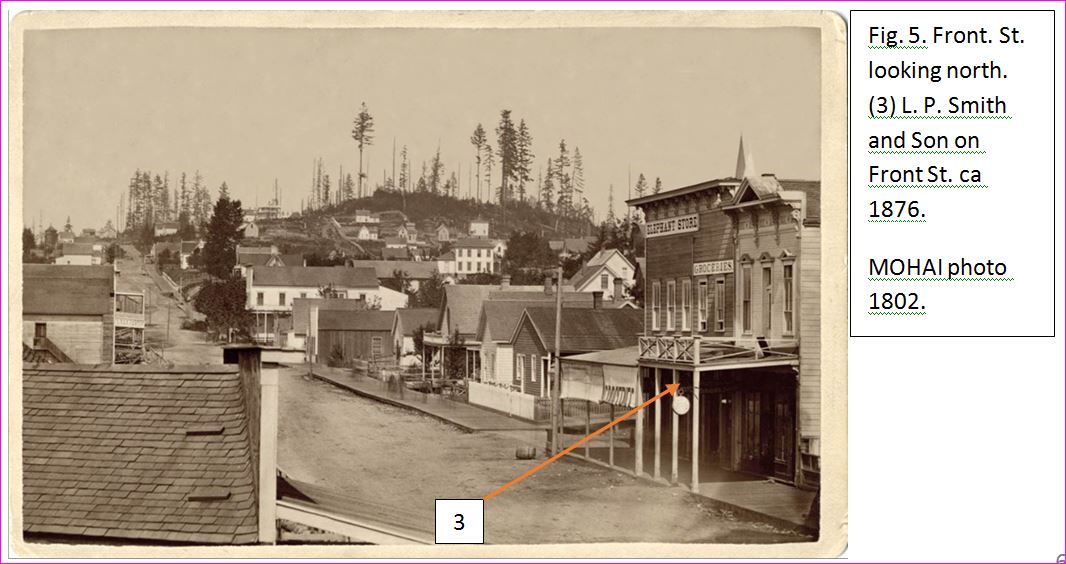

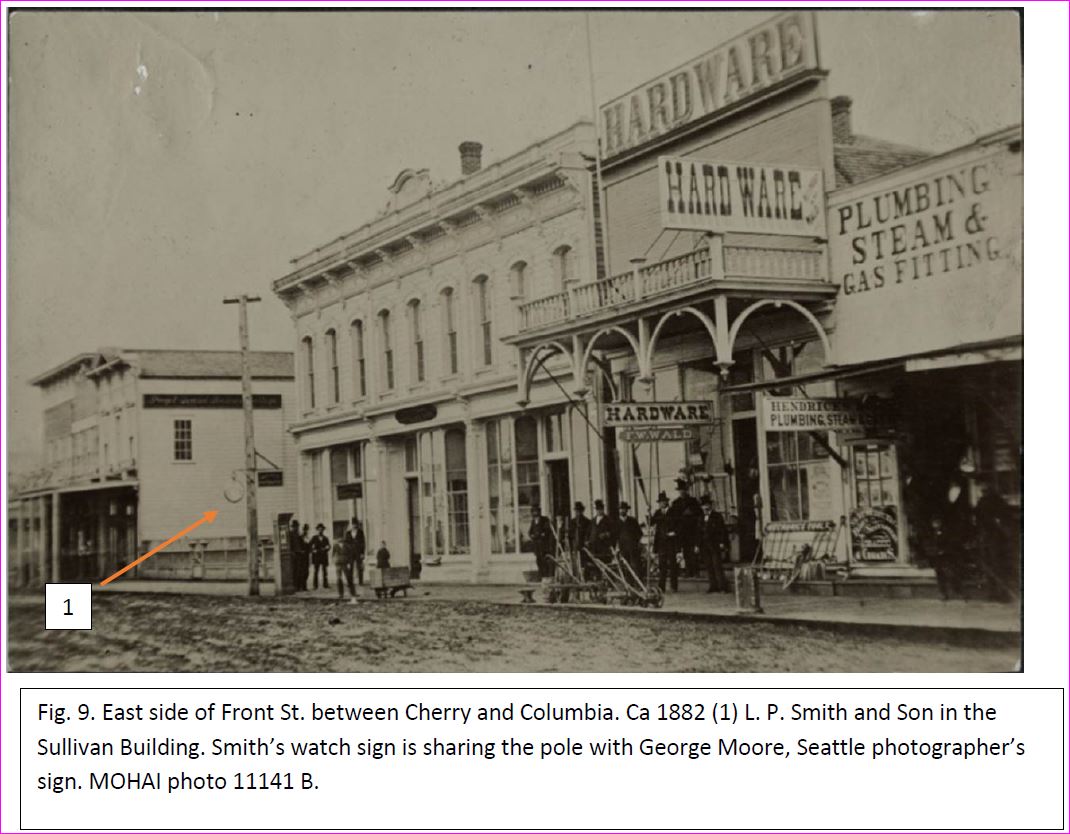

An 1872 Puget Sound directory lists Smith on Mill St. next to the

Intelligencer building. Parker moved to Olympia by 1872. Sometime

after 1872 Smith moved his business out of Seattle for a short time but

we don’t know where. An 1876 newspaper ad says he moved back to

Seattle. His business now, L.P. Smith and Son, was located on Front St.

in Reinig’s Building opposite the brewery. Fig. 5. The son,

Alfred A. Smith, now his father’s partner, and his wife were living

with his parents in 1880. The Smiths moved a few yards south to

Sullivan’s Block on Front St. sometime before 1879 where they remained

in business until 1887. Figs. 6 and Fig. 9.

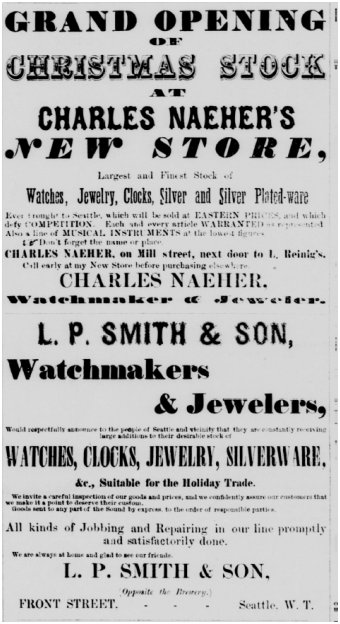

Fig. 3. Above: Seattle Daily Intelligencer Dec. 11, 1876

Left: Daily Intelligencer Sep. 29, 1876

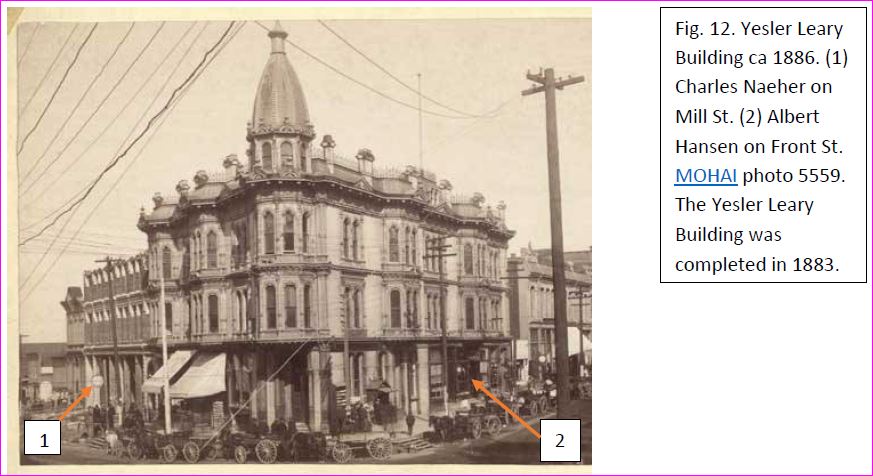

William G. Jamieson and Charles Naeher (Naher) were both listed as

jewelers in the same 1872 directory on Commercial St . Figs. 2, Fig. 3,

Fig. 4. Jamieson immediately launched an aggressive advertising

campaign. Naeher, a 43 year old German immigrant, left a jewelry

business in St. Paul, MN. Both his sons worked for him, one as a clerk

and the other a watchmaker. Naeher moved to Mill next door to Rienig’s

Bakery in 1876. (Mill near Front), and into the Yesler Leary Building

on Mill St. in 1883. He remained in business until his death in about

1890. His elder son became a vice president of

Schwabachers, Seattle’s

first and for many years, premier department store and hardware

wholesaler.

Seattle’s First Public Clock

Based on the size and number of ads (1876-1879), W.G. Jamieson tried to

be the largest and most competitive jeweler. In 1877 he was

occupying two brick fireproof stores on the corner of Commercial and

Mill Streets with his “Jewelry, Music and Art Emporium” and claiming to

be largest business of its kind north of San Francisco. He advertised a

wide variety of goods in addition to jewelry, silverware, watches and

clocks. These included books, stationary, musical instruments and agent

for the Singer Sewing Machine Company. October 1877 found him posting

notices pleading for people to pay their bills. In January 1878 he

announced a move to the Masonic Hall on Front St. Fig. 1. In February

of 1878 the Intelligencer reported he had installed a “transparent

magic clock” in his window with a reflector behind it and between them

a calcium light. “It is the next best thing to a town clock that could

have been devised.” Jamieson went into receivership April 18, 1878 in

spite of his innovative public timepiece.

Time by Telegraph

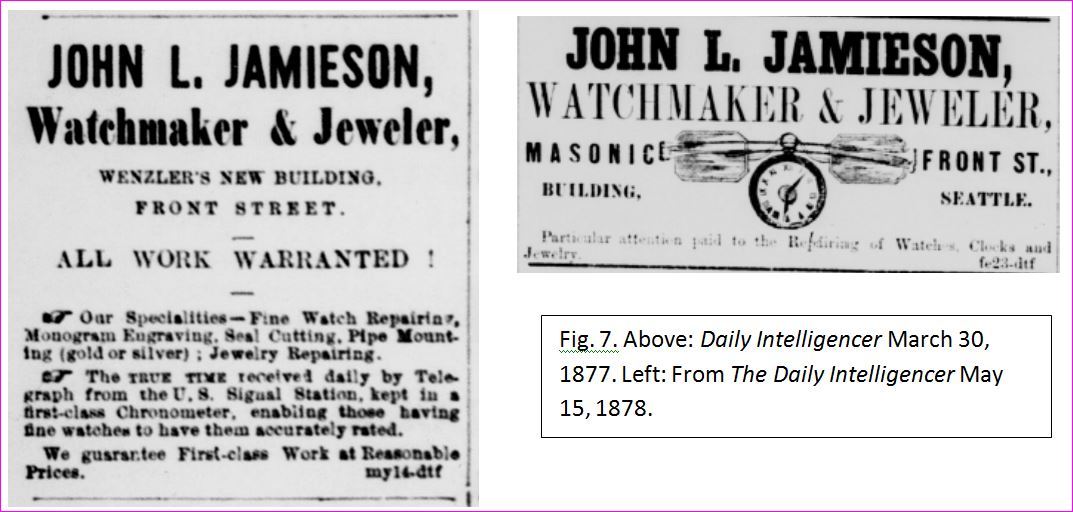

William’s younger brother, John L. Jamieson showed up on the pages of

the Daily Intelligencer in June of 1876 advertising as a Book,

Stationary and Tobacco store next to Schwabachers on Commercial St.

November 1876 ads place him in Coleman’s brick building, Mill St. Fig.

7 An 1876-78 Pacific Coast Directory lists him as a jeweler on

Mill St. January 1878 found him sharing quarters with his brother in

the Masonic Hall on Front St. In May 1878 he ran a very

interesting ad as a watchmaker and jeweler in Wentzler’s new building

on Front St. His specialty is in watch and jewelry repair. He states

that “The true time is received daily by telegraph from the U.S. Signal

Station and kept by a first class chronometer, enabling those having

fine watches to have them accurately rated.” This is the first

indication I have of a jeweler using time by telegraph in Seattle and

making it available to the public. This service was short lived. His

last ads appeared in September 1878

U.S. Signal Stations were established as meteorological observatories.

The Army’s Chief Signal Officer reported that a station had been

established in Olympia, W.T. in 1878. In 1870, the Signal Corps

established a congressionally mandated national weather service.

This included a network of weather observatories called U.S. Signal

Stations. Some of the more famous included ones on top of Mt.

Washington in New Hampshire and Pikes Peak, Colorado. By 1879 the

Signal Corps had constructed, and was maintaining and operating, some

4,000 miles of telegraph lines connecting the country's western

frontier. The Signal Stations reported their results by this

system. The Signal Service master clock telegraphed Naval Observatory

Washington time signals to the Signal Stations, coordinating the

observations. Jamieson’s is the first known example of these

signals being distributed to private users. Note that this predates by

several years the adoption of standard time zones or the routine

distribution of time signals by Western Union.

John Jamieson’s last ad in the Intelligencer ran Sep. 27, 1878. An 1879

directory lists him as a jeweler on Cherry between Front and

Second. The 1880 census finds both James and his brother, William

working as watchmakers in Walla Walla, probably for Zebulon K. Straight

Walla Wall’s most prominent watchmaker.

Jewelers from 1882-1889

Five jewelers were listed in 1876. Smith, Naeher and the Jamieson

brothers had been joined by William Hanson specializing in repair only.

Hanson disappeared within a year or two. The Jamieson’s had both moved

on by 1879. Seven jewelers were in business by 1882 and nine in 1884.

Smith and Naeher also advertised as wholesale jewelers for the first

time in 1884.

William H. Finck arrived in 1882 and opened a jewelry store on

Commercial St. opposite the New England Hotel. Finck was a 24 year old

Canadian immigrant, son of a German father and Canadian mother. He was

working as a jeweler in Oroville, California in 1880. Finck established

a successful and long lived business. He would eventually install a

street clock which stood in front of his store until he retired in 1913.

H.J. Requa, a 25 year old native of Wisconsin showed up first as a

jeweler in 1882. He was in partnership with A.E. Giering in 1884. By

1888 they went their separate ways; Giering in partnership with Charles

O’Donnell; Requa in several locations. Fig. 11.

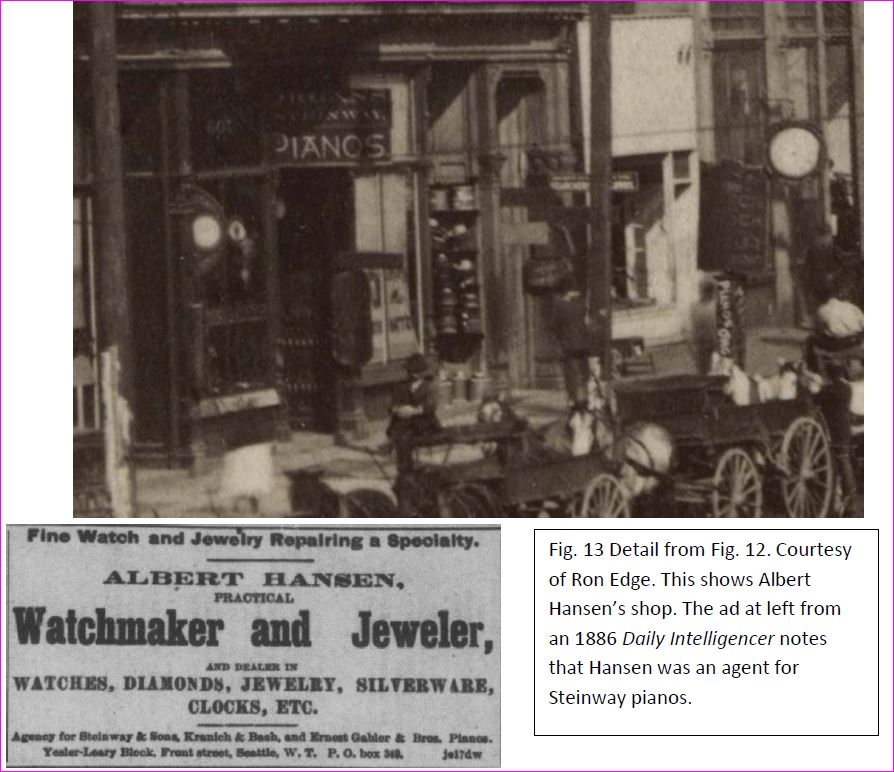

The Yesler-Leary block, Seattle’s most substantial pre fire commercial

building, opened in 1883. It occupied the southwest corner of Mill and

Front St. Charles Naeher moved into the Mill St. side. Albert

Hansen opened his jewelry store in 1884 on Front St. in the Yesler

Leary block. Fig. 12. Albert was born (1857) and raised in

Denmark of a German father and Danish mother. He and his two older

brothers, Theodore and Rudolf, immigrated in 1879. All three were

jewelers. They went first to California where the oldest brother,

Theodore married and started a family. Albert never

married. Hansen would install one of Seattle’s first

street clocks in 1890. He and Theodore opened stores in Spokane and

Tacoma about the same time where they also installed identical Seth

Thomas clocks. These stores did not survive the financial panic of

1893. They consolidated their business in Seattle which then grew into

one of Seattle’s largest and most well respected jewelry stores,

continuing in business until 1930.

Time from the sun and stars

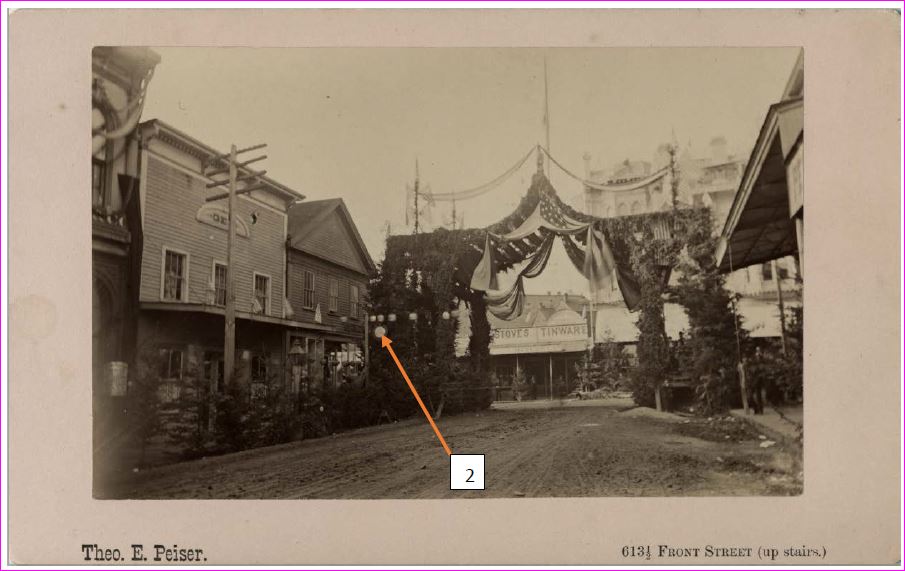

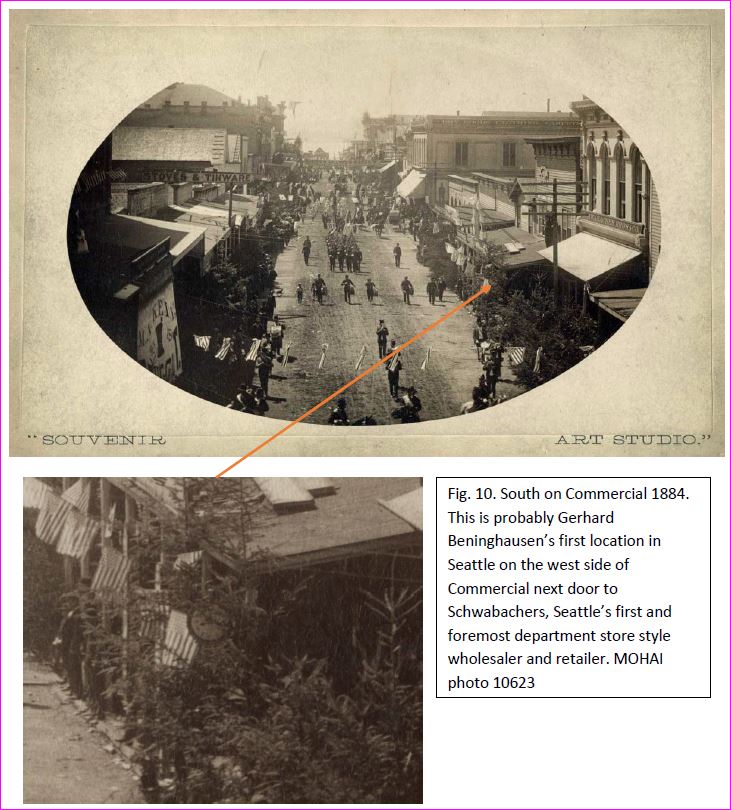

Gerhard Beninghausen, a German immigrant, worked for Kimball and Son

upon his arrival in 1883 and established his own business in 1884.

Beninghausen’s first location was on the west side of Commercial

between Washington and Mill. Fig. 10.

Beninghausen was a serious watchmaker. He is the first Seattle

watchmaker to repair and rate chronometers, an important service in a

town that wanted to be a major seaport. He took daily

observations of the sun and stars for local time. Telegraphic time was

not routinely available in Seattle until about 1890. This underlines

J.L. Jamieson’s pioneering telegraphic efforts in 1878. Fig. 8

Beninghausen had a very successful jewelry business which he sold in

1905. His store front was distinguished by Seattle’s only street time

ball. A few years later he reopened as a watch and chronometer

repairer and continued until his death in 1922.

Fig. 8. From Seattle Post

Intelligencer Feb 21, 1887

Jewish Jewelers in Seattle

Joseph Mayer arrived in 1883 at age 15. He would eventually found

a wholesale jewelry and jewelry manufacturing company that would become

the largest on the West Coast. His 1883 arrival in New York from

Germany was just in time to take advantage of the Northern Pacific

railroad’s first connection to the Northwest, from St Paul, Minnesota

to Portland and Tacoma. This event shortened a journey which might have

taken weeks or months into one of a week or so. Mayer probably

completed the journey either on a steamer from Tacoma or on the Puget

Sound Shore Railroad.

Seattle was a brawling frontier village that had just passed Wall Walla

to become the territory’s largest town. It was well on its way to

becoming a city of over 12,000 people engaged in lumbering, fishing,

shipping and wholesale trade. Seattle saw 1000 new homes built in 1884.

The city was riven with ethnic violence by the anti-Chinese riots in

1885-86. The territorial governor placed Seattle under martial law for

a period. Lynching was not unheard of during this relatively lawless

period.

Joseph joined a Jewish community of 100 or so. Many, like

himself, were German speaking from central Europe, some of whom were

very successful entrepreneurs. These included Bailey Gatzert, manager

of Schwabacher Brothers general wholesale and retail store. He became

mayor of Seattle in 1875.

Henry E. Levy, a 35 year old New Zealand immigrant, established a store

on Commercial St in 1876. He called it “The Seattle Bazaar”

specializing in glassware and pottery. An 1888 gazetteer lists

him also as a jeweler. There is no indication that he was a watchmaker.

Morris Abram, was a pawnbroker on Mill St. in 1882. Jacob Levy and his

family make their first appearance in 1888 as a tailor and pawnbroker

at 206 Commercial. His 19 year old son, George F. Levy, was working as

a watchmaker for Frisch Brothers Jewelers (Norwegian immigrants) in

1888 and then the following year for his father. George was apparently

in delicate health and attempted suicide in 1891. He survived and

worked periodically for Frisch Brothers and independently over the next

several years.

None of these seem very likely as employers for Joseph Mayer who would

have needed to continue his apprenticeship as a watchmaker. Charles

Naeher and Gerhard Beninghausen were the only native German speakers

with their own businesses that might have employed Mayer. Simon

Rumpf, a German Jew, arrived in 1886 and worked a short time for

Beninghausen. Rumpf would eventually become Mayer’s ill-fated partner

in his first independent enterprise as a pawnbroker and wholesale

jeweler. Naeher was nearing retirement so Beninghausen seems the most

likely to have taken Mayer in.

Joseph was joined by his younger brother, Albert, age 15, who arrived

in Seattle July 1, 1888. The 1889 directory lists 12 watchmakers

and jewelers and four pawnbrokers. Neither Joseph nor Albert appears in

this directory.

Nathan Phillips, an orthodox Jew, age 23 arrived in Seattle in 1888. He

is the first eastern European Jewish watchmaker that I can document in

Seattle. An 1890 directory lists him as a “Peddler”. In 1892 he is

listed as a jeweler and in 1893 he is listed under Clocks, Watches and

Jewelry at 207 Washington, just across the street from Rumpf and

Mayer’s Uncle Harris Pawnshop. (204 Washington). 1894 and ’95

directories list him as Boston Loan Office at 214 Washington.

Phillips was apparently in the habit of taking a selection of watches

and jewelry to the mining camps east of Seattle. June 29, 1896 found

him on such a trip, staying at the Monte Cristo Hotel in Monte Cristo

Washington. Monte Cristo, now a ghost town in eastern Snohomish County,

was the first silver mining center on the western slope of the

Cascades. By 1893 there were over 200 claims. John D. Rockefeller had

bought up a controlling interest in most. The Monte Cristo Hotel and

associated brothel was owned by Frederick Trump, the Donald’s

grandfather. A rapscallion named David Leroy approached Phillips at the

hotel with a watch to repair and lured him to the outskirts of town

with the promise to connect him up to someone who wanted to buy a

watch.

As they approached Leroy’s home, the thief demanded Phillips’ satchel

containing $1000 worth of watches and jewelry. Before Nathan could

comply, Leroy drew his gun, fired, knocking Phillips to the ground.

Leroy shot him again, this time through the back. Witnesses later

stated they saw Leroy and his brother heading for the high timber

carrying a rifle and a brown satchel. Phillips, in very bad shape, was

taken back to the hotel where he was given some rudimentary first aid

for his injuries. The following day his brother and two doctors arrived

by train from Seattle. Phillips was treated and returned to Seattle

where he recovered at Providence Hospital.

The hotel landlord retrieved Phillips blood stained vest where he found

the watch given to Phillips by Leroy. It had stopped the first bullet,

saving Phillips life. The newspaper account described Phillips as

standing high among the merchants of Seattle with a most excellent

reputation among the Jewish citizens. They noted he had been in the

loan business for the past four years.

Phillips moved his business to 106 Occidental in 1898. He married

Johanna Brooks, the daughter of the first rabbi of the Bikur Cholem

congregation, that same year. Bikur Cholem, the first orthodox

synagogue in Seattle, was dedicated in 1898.

Nathan Phillips passed away at age 38, June 11, 1903. He left a family.

He had been in poor health for some time probably aggravated by his

near death experience in Monte Cristo. His business continued at 821

1st Ave. A number of pocket watches survive with his name on the dials

and movements.

City directories for 1890 and 1891 show Joseph, now 21, working as a

watchmaker for Augustus Franklin, a pawnbroker, at 204 Washington St.,

just around the corner from Albert at 207 3rd Ave. The directory

entries for both imply that they were living at the same address they

worked. Franklin appears only in the 1890 and 1891 directories and

disappears the next year.

Albert was working for “M. W. or M. M. Fredrick” at 207 S. 3rd Ave,

rooming at the same address. Morris M. Fredrick is listed as a jeweler

rooming at that address. Morris, also a German Jew, was born in 1837,

immigrated in 1853 and by 1880 was living in Virginia City, Nevada,

listed as a jeweler. He married Anna in 1859 and they had a son, Marcus

W. born in 1863. Morris and his family moved on to San Francisco

where he became a manager for Will and Finck, well known manufacturing

cutlers. The 1891 directory lists Marcus W. Fredrick (Fredrick and Co.)

at 207 3rd, still boarding at the same address. Morris was probably

dividing his time between San Francisco and Seattle. He was still

listed as a Vice President of Will and Finck in 1896. A 1909

Seattle Times social page report of his 50th wedding anniversary refers

to him as a pioneering Seattle jeweler who arrived in the city in

1889. His son, Marcus may have managed Fredrick and

Co. for the first few years, eventually returning to San Francisco

where he was listed in 1909 as an “oculist and aurist”. This is

consistent with the family memories of Janet Levy, Albert Mayer’s

granddaughter, recorded in 1972. Her grandmother, Leah, used to talk

about her grandfather learning watchmaking from Mr. Fredrick. She

stated that her grandfather became a fine watchmaker. Morris

Fredrick was the first really successful Jewish jeweler in Seattle. He

moved to 2nd Ave. in 1894, taking over a store with a Howard street

clock which had come to the city the year before.

Joseph and Albert Mayer are among the first Jewish watchmakers to

arrive in Seattle that I can identify. Both probably received some

apprentice training in Germany before emigrating and then completing

their apprenticeships in Seattle. They went on to found a great jewelry

manufacturing and wholesale house in 1897.

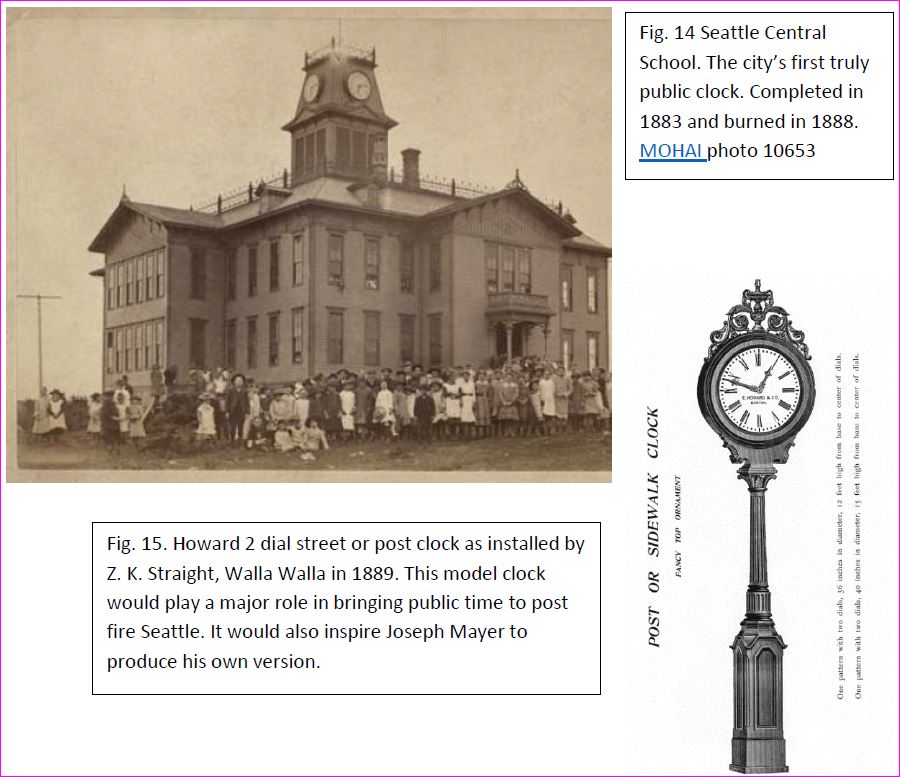

The First Tower Clock in Seattle

Only one actual public clock greeted Joseph Mayer upon his arrival in

Seattle. Seattle’s Central School, the largest public school in the

Washington territory, was completed in 1883. It sported a four

dial tower clock of unknown make. There is no record of it in E. Howard

Clock Co., Boston or Seth Thomas, Thomaston, CT records. These two

companies supplied the vast majority of public clocks across the

country after 1870. The school burned in 1888 and the building which

replaced it had a tower with dial like openings but no clock. It would

be almost twenty years before Seattle saw its next tower clock. Fig.

14.

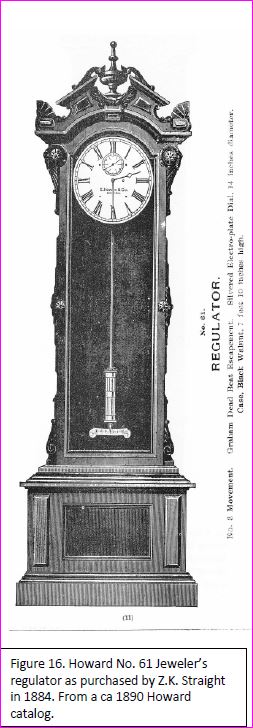

Distributing Standard Time in Walla Walla

The earliest standard public time in the Washington Territory was

probably supplied to the citizens of Walla Walla by

Zebulon Kenyon

Straight, one of the most prominent jewelers in the Territory.

Straight opened his business in 1870 after training as a watchmaker in

Minneapolis. On April 16, 1884 he ordered a top of the line clock from

Nordman Brothers, a San Francisco agent for the E. Howard Clock

Co. This was shipped from Boston, completing its journey via the

Northern Pacific Railroad. The line had just been completed the

previous year, connecting St. Paul, Minnesota to the Washington

Territory and Portland. The clock was a Model No. 61 regulator,

standing over seven feet tall in an imposing carved black walnut case

Fig. 16. The movement was fitted with jeweled pallets and a temperature

compensated, mercury pendulum. The glass door proudly proclaimed “City

and Railroad Time”. An 1889 catalog lists this clock for $350

plus shipping. . Routine telegraphic time signals from the Naval

Observatory would not be available for several more years. Straight

must have used a small telescopic transit instrument and calculated

local time based on sun and star sights. He would then correct these

observations to the meridian for the Pacific Time Zone. citizens of Walla Walla by

Zebulon Kenyon

Straight, one of the most prominent jewelers in the Territory.

Straight opened his business in 1870 after training as a watchmaker in

Minneapolis. On April 16, 1884 he ordered a top of the line clock from

Nordman Brothers, a San Francisco agent for the E. Howard Clock

Co. This was shipped from Boston, completing its journey via the

Northern Pacific Railroad. The line had just been completed the

previous year, connecting St. Paul, Minnesota to the Washington

Territory and Portland. The clock was a Model No. 61 regulator,

standing over seven feet tall in an imposing carved black walnut case

Fig. 16. The movement was fitted with jeweled pallets and a temperature

compensated, mercury pendulum. The glass door proudly proclaimed “City

and Railroad Time”. An 1889 catalog lists this clock for $350

plus shipping. . Routine telegraphic time signals from the Naval

Observatory would not be available for several more years. Straight

must have used a small telescopic transit instrument and calculated

local time based on sun and star sights. He would then correct these

observations to the meridian for the Pacific Time Zone.

Straight was the first in the Washington Territory to add a two dial

post or street clock to his business on Walla Walla’s Main Street. Fig.

15. He chose one from Seth Thomas’ principal rival, E. Howard

Clock Co. Boston. Ordered May 18, 1889, the first street clock in

Washington cost $300 delivered from the Chicago office of E. Howard via

the Northern Pacific. Fig. 14. Later that same year

Washington became a state with Zebulon K. Straight as a member of the

first state legislature

Conclusion

Seattle’s first jewelers are an interesting mix of mature, experienced

and probably well capitalized men and young entrepreneurs. Smith and

Naeher both were in business with their sons. They survived the

national financial crisis of the 1870’s and continued until retirement

in the late 1880’s. Smith’s son continued in business for a short time

and then disappeared. Naeher’s oldest son became a vice president of

Schwabachers. The Jamieson brothers never seemed to be in business

together except for a short period when they shared premises in the

Masonic Hall. William used extravagant advertising and apparently

stocked a wide variety of goods including sewing machines and musical

instruments. He was probably too generous in extending credit and went

into receivership. That he and his brother were competent watchmakers

would be attested to by their eventual employment with Zebulon K

Straight, Walla Walla’s leading jeweler.

The second wave of jewelers arriving in the 1880’s included several who

would survive the great fire, June 6, 1889. The early history of

Seattle is starkly divided by this event. By the morning of June

7, the fire had burned 25 city blocks, including the entire business

district, four of the city's wharves, and its railroad terminals.

1889 found 12 jewelers in business. Seven remained in business

following the fire. Among these were William Finck, Albert Hansen,

Gerhard Beninghausen and W.W. Houghton, all of whom grew into

substantial businesses lasting well into the 20th century. They also

all eventually had street clocks obtained from Joseph Mayer. The rapid

recovery and complete rebuilding of Seattle’s commercial center in

durable brick and stone attracted craftsman and entrepreneurs. The

number of watchmakers and jewelers listed doubled from 16 in 1890 to 32

in 1891.

Among the young jewelers working in Seattle before the fire was one

Thomas J. Carroll, born in Beaver Dam Wisconsin and trained as a

watchmaker in Buffalo, N.Y. He came first to Port Townsend and then to

Seattle in 1888, attracted by a weekly wage for watchmakers of $19 per

week, double what he could make in New York State. These wages

illustrate the imperative many young watchmakers felt to establish

their own businesses. Carroll worked for G.G. White and Co. who

had just opened their business. Barely a year later, alerted to the

approaching fire, he packed a piano crate with watches, diamonds and

jewelry, loaded it on a buggy and took it up the hill out of reach of

the flames. Despite Carroll’s effort White disappeared from the scene

shortly after the fire. By 1895 Carroll had saved $200, enough to open

a tiny, one showcase store. , His business prospered and

the family continued it throughout the 20th century. His street clock,

made by Joseph Mayer in 1930, became a Seattle downtown icon and is now

preserved at the Museum of History and Industry.

Joseph and Albert Mayer survived the fire, teaming up to bring public

time to the streets of the West in the next century. Morris Fredrick

remained the most prominent Jewish jeweler, retiring in 1909. Many of

Seattle’s great jewelry houses were founded by Eastern European Jews in

the first quarter of the 20th century. These included Burnett Brothers,

Friedlander’s, Weisfield and Goldberg and Ben Bridge. The Ben Bridge

chain remains with 85 stores throughout the western United States.

Acknowledgements:

I would like to thank Ron Edge, Seattle historian, for bringing several

of these pictures to my attention.

1 M.L. Sammis Panorama, 1865, http://pauldorpat.com/2009/06/25/seattle-waterfront-history-chapter-six/

2 A numbered key to Sammis Panorama. The building was identified as

Welsh & Greenfield Clothing in 1865. https://sherrlock.files.wordpress.com/2015/10/kellog-sammis-pan-numbered-keyweb.jpg

3 Washington Standard, Olympia, W.T., March 5, 1864

4 Pacific Coast Business Directory, Henry G. Langley, San Francisco,

1867, p. 550 https://archive.org/stream/cihm_17457#page/n823/mode/2up

5 Pacific Coast Business Directory, Henry G. Langley, San Francisco,

1871. P. 388 Ron Edge reference.

6 McCrossen, Alexis, Marking Modern Times, A History of Clocks, Watches

and other Timekeepers in American Life, University of Chicago Press.

This book provides an excellent overview of the origins and

consequences of an awareness and synchronization of public time.

7 Report of the Superintendent of the U.S. Coast Survey During the Year

1871, Washington, 1874 p.63

8 Daily Intelligencer, Seattle, Sep. 28, 1876

9 Puget Sound Directory and Guide to Washington Territory 1872, Murphy

& Harned, Olympia, “First year of publication”

10 Report of the Chief Signal Officer to the Secretary of War, Reports

of the Secretary of War, 1879, p. 80. Station at 47o 2’ N., 122o 56’ W.

in the second floor of the Granger Building corner of Main and Fifth

Streets. http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=osu.32435062856117;view=1up;seq=86

11 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Signal_Corps_(United_States_Army)

12 Bartky, Ian Selling the True Time, Stanford, 2000, p. 101

13 Private communication with Professor Alexis McCrossen, Southern

Methodist University.

14 Web site: HistoryLink.org

Essay 1965

15 Cone, Droker, Williams, Family of Strangers, Washington State Jewish

Historical Society, 2003

16 Morning Oregonian, Portland, OR, Sep. 12, 1888

17 U.S. Passport Application for Albert Mayer 1906

18 U.S. Federal Census 1880 and 1900

19 Polk’s San Francisco City Directories

20 Seattle Sunday Times, September 19, 1909

21 Interview with Janet Levy Feb. 15, 1972 Manuscripts & Univ.

Archives Div. University of Washington Libraries

22 http://www.historylink.org/index.cfm?DisplayPage=output.cfm&file_id=10482

23 Howard Records digitized by National Association of Watch and Clock

Collectors (NAWCC) Series 7 Clock Orders 1881-1887, p. 85. McCrossen

(p. 122) mistakenly assigned this order to Nordman Brothers who were

San Francisco agents for Howard. The order makes it clear that the

clock was destined for Z. K. Straight, one of Washington Territory’s

first jewelers.

24 Howard Records Tower Clocks Series 1 1888-1901, p. 16

25 Seattle Sunday Times, June 23, 1935

26 Brazier, Dorothy Brandt, Time Marches on for the Carroll Family

27 Glover, E.S., Birds-eye View of the City of Seattle, 1878, Library

of Congress, Geography and Map Division

28 Stoner, J.J., Madison, WI, Birds-eye View of the City of Seattle,

1884, Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division

|