|

|||||||

|

|||||||

Joseph Mayer, the Dexter Avenue Clock and the Brothers Caplan and KaplanBy

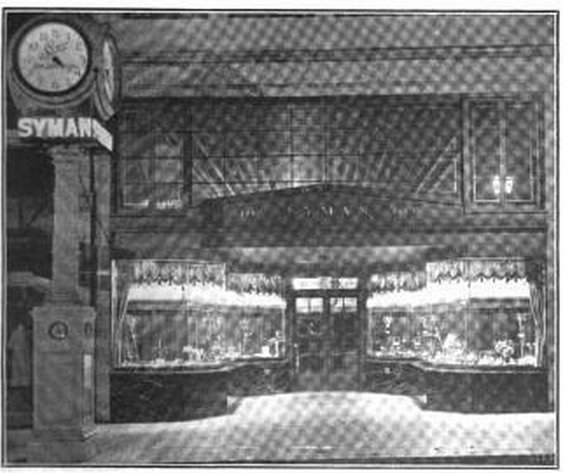

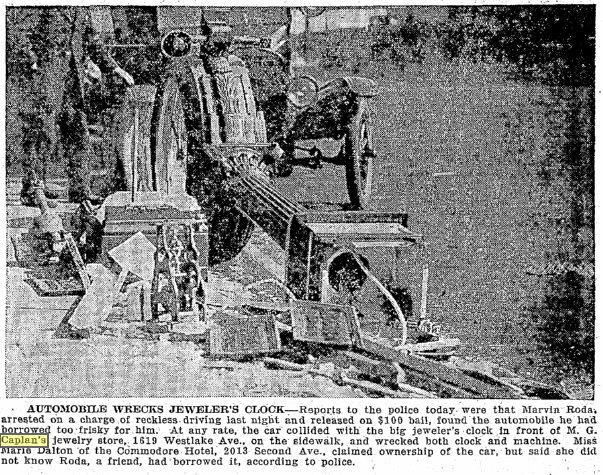

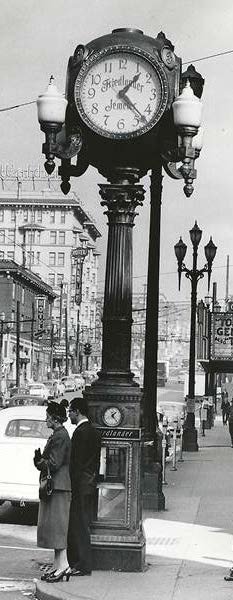

Paul Middents FNAWCC IntroductionOn a mercifully dry February 12, 2015, a significant work force gathered in Seattle’s South Lake Union neighborhood on the corner of Dexter and Harrison. (Fig. 1) The object of this group was the removal of a large street clock which had stood in this spot since 1939. Larry Johnson, architectural history consultant to the developer, documented the removal on his blog, Feb. 14, 2015. Chuck Roeser, Essence of Time, was also present for the removal in an official consultant capacity. Ultimately we hope he will be restoring the clock. The most exciting revelation was the discovery of a jeweler’s name still faintly visible on the dials when closely examined after removal.The clock is being saved as part of the redevelopment of this area. The developer is being required to salvage, restore and reinstall the clock near its original location because nine of Seattle’s surviving street clocks were designated as historic landmarks in 1981 1. 406 Dexter Ave. and its HistoryThe building at 406 Dexter was occupied by Seattle’s only street clock maker, Joseph Mayer in 1936. He had moved from his factory in the Colman Annex at 81 Marion where he had been since 1905. Mayer reincorporated as Northern Smelting and Refining Co. in November 19352.Mayer’s earliest street clocks began to appear in 1909. By 1935 he had produced over 100 street clocks, at least 40 of which once stood in and around Seattle. Others could be found in cities and towns all over Washington, Oregon, Nevada, Montana, California and British Columbia. By 1936, the heyday of the street clock had passed and Mayer had business and health problems all of which contributed to death by his own hand August 7, 1937 3. On February 16, 1938 Northern Smelting and Refining became Northern Stamping and Manufacturing Co. It was incorporated by Ned Thompson, B.L. Culbertson and P.E. Thompson to deal in precious metals.4 In November 1939 a Seattle street use permit was signed by Paul Costello, Vice President, to move an eight dial street clock to 406 Dexter Ave. The below ad appeared in a 1943 Jeweler’s Circular directory. This would indicate National Stamping continued using the Joseph Mayer mark on flatware and souvenir spoons. They also used the “NS” mark, probably on new designs. Northern Stamping was bought out in 1945 and became E.J. Towle Co. still located at 406 Dexter. Both Northern Stamping and E.J. Towle concentrated primarily on silver flatware and souvenir spoons. Both firms retained over 14,000 hand sunk dies for spoons, fraternal emblematics and medals. Towle used the “EJT” mark on spoon designs they originated. In the 1960’s and 70’s they reissued at least 42 Mayer designs.5 These usually had a new bowl design---narrower than the original Mayer spoons.  In 1980 Charles B. Cantrell in

partnership with Raoul Leblanc purchased

E.J. Towle. They renamed the company West Earth, Inc. and continued the

business at 406 Dexter. LeBlanc issued a catalog in 1981 listing many

of the spoon dies and offering some of them for sale.6

Apparently

Towle retained title to the dies and was leasing them to LeBlanc. Many

of the original dies were sold to collectors. The West Earth

trademark incorporated the “WE”. In 1985, Cantrell bought out

Raoul Leblanc and named the company Metal Arts Group. In 1980 Charles B. Cantrell in

partnership with Raoul Leblanc purchased

E.J. Towle. They renamed the company West Earth, Inc. and continued the

business at 406 Dexter. LeBlanc issued a catalog in 1981 listing many

of the spoon dies and offering some of them for sale.6

Apparently

Towle retained title to the dies and was leasing them to LeBlanc. Many

of the original dies were sold to collectors. The West Earth

trademark incorporated the “WE”. In 1985, Cantrell bought out

Raoul Leblanc and named the company Metal Arts Group. Most of the original belt driven equipment was still in place at 406 Dexter when it was demonstrated to a national souvenir spoon collector convention in 1992. Metal Arts was purchased by J. H. Recognition Co. of Portland, OR in 1999 and all activity was moved to Portland. The Metal Arts Co. web site still traces its ancestry to Joseph Mayer.7 The Eight Dial ClocksThe ultimate street clocks built by Joseph Mayer are the monumental eight dial models. These clocks, standing over 20 feet tall, featured a unique set of four dials at pedestrian eye level arranged around the top of the base. Some had sweep seconds hands and some seconds dials at the “6”. Mayer designed his own version of an E. Howard movement which featured a Denison gravity escapement, temperature compensated pendulum and Mayer patent electric winding system. The clocks were state of the art and cost at least $3,600 in 1922.8 (Over $50,000 today). Six clocks of this type have been identified so far, of which three survive. The first of these clocks built for Albert Samuels, San Francisco jeweler, in 1915 survives on Market Street in nearly original condition.9 (Figs. 2 & 3) This clock was restored by Jack Wittenmyer in 2000.10 Weisfield & Goldberg, Seattle jewelers, purchased one in 1919. It was last seen in 1967. Arthur Syman, Tacoma jeweler, installed one in 1921.11 Its fate is unknown. (Fig. 5) The American Jewelry Co., Bakersfield, CA purchased one in 1922. It remained in Bakersfield until just a few years ago when Jasper San Filippo purchased it. It is now beautifully restored as part of the San Filippo collection in East Barrington, IL at "Place de la Musique.” (Fig. 3) The last recorded eight dial clock was made for the Seattle jeweler, Friedlander June 28, 1928 and last seen in 1950.12(Fig. 13) The clock I originally tried to associate with the Dexter Ave. clock was documented in a Seattle Street Use permit issued to Gus Cohn March 16, 1928 for the installation of a Mayer eight dial clock in front of his shop at 310 Pike.13 The permit refers to the dials having the name Allan which would be changed to reflect the new owner. Allan was a prominent Vancouver, B.C. jeweler. Cohn installed a Mayer two dial late production model clock at 1421 4th Ave in 1925. All the photographic evidence shows that he installed the two dial clock at 310 Pike in 1928 and not an eight dial clock. (Fig. 10 & 11) Based on the dates of the Friedlander and Cohn applications, it is probably that the eight dial clock orginally intended for Cohn was purchased by Freidlander. The Dexter Ave. clock is one of three surviving examples. The origin of the clock was a mystery until the dials were removed as a part of the Feb. 12 process. These revealed the name “M.G. Caplan Jeweler” which had been partially excised. Caplan and KaplanMoshe (b. 1877) and Smole (b. 1884) Kaplan were born in Russia and apprenticed at age 13 to watchmakers. Smole and his wife Minnie immigrated to Seattle in about 1918, Moshe a few years earlier. Smole became Sam and Moshe, who never married, became Morris and eventually Maurice. He also changed the spelling of his last name to Caplan. Morris was working as a watchmaker in 1918 in the Green Building and the following year in the Pantages Building. By 1920 Morris had his own business at 1619 Westlake and within a year or two Sam opened his own shop at 1318 1st Ave.Morris installed a Joseph Mayer two dial street clock (late production style) in November 1922. It survived a record snow storm Feb 14, 1923 (Fig. 6) and then came to an unfortunate end when struck by a car June 4, 1923. (Fig. 7). A Seattle City Department of Streets and Sewers street clock inventory dated Jan. 10, 1924 does not list a clock for 1619 Westlake. The next inventory dated July 29, 1927 does. 14(Fig. 8) 14 Caplan must have replaced the two dial clock with one of Mayer’s eight dial models probably shortly after this loss sometime in 1924. Photographic evidence for this clock is sparse but fortunately a real photo postcard (RPPC) overhead shot of Westlake Ave. from the mid 1920’s clearly shows the big round head clock. Morris was issued a street use permit March 28, 1930 to move his clock. In May Morris moved his business to a street level location at 206 Pike. (Fig. 9) He increased his newspaper advertising profile, apparently hoping for more business closer to the heart of the jewelry retail trade in Seattle. He brought his big clock with him where it joined a number of other Joseph Mayer productions. (Fig. 11) These included the Weisfield & Goldberg eight dial clock two blocks up at 414 Pike and Friedlander’s eight dial (identical to Caplan’s) across the street and up the block at 5th and Pike. Ben Bridge, across the street at 4th and Pike installed a Mayer four dial clock in 1928 which is the lone survivor on what was once a great street of clocks. Thomas Carroll, who as one of the first tenants in the Joshua Green Building, across the street at 323 Pike installed a “hand-me-down” Seth Thomas two dial clock in 1913. This was one of Seattle’s first two street clocks, purchased by Albert Hansen in 1890. Carroll must have finally felt compelled to upgrade this clock with the arrival of Caplan in 1930. He replaced it that same year with the last documented four dial clock made by Joseph Mayer. This clock survives at the Museum of History and Industry. December 1930 found Caplan advertising a “Creditors forced sale of jewelry 20% to 50% off”. June 5, 1932 The Seattle Times reported that Caplan was "arranging for a planned removal to other quarters following an auction sale the past week." He moved to the second floor in this same building, 303 Peoples Bank Building. Adding insult to injury, they also reported that he had been robbed of $1000 worth of diamond rings the previous day while moving upstairs. Morris remained in business at this location until 1956. A June 22, 1932 letter from the Superintendent of Public Works to the Board of Public Works reported that the new tenant of 206 Pike complained of the street clock left by Caplan in front of their business and wanted it removed. The letter also noted that Caplan was financially challenged and would find it difficult to pay for the removal. Joseph Mayer had been approached and agreed to remove the clock within 15 days. The board directed the removal. A July 4 letter from Mayer to the Board reported that Caplan had countermanded the Board’s order for removal by July 5 and the city had directed him to proceed. Mayer requested an additional 15 day extension and stated that he would remove the clock “putting it in storage in our plant holding it subject to the charges for our labor”. The board granted Mayer’s 15 day extension. The clock was removed probably by early August. The following advertisement appeared in the May 26, 1937 Seattle Times: The ad clearly refers to an eight dial clock based on the orginal cost of $3500. This may have been either Caplan trying to sell his clock or Mayer trying to sell it to recapture removal and storage fees accruing since 1932. That is the last we hear of it until 1939. Mayer must have retained the clock, never having been compensated for the removal. It must have been discovered by his surviving partners and taken out of storage. Meanwhile, Sam Kaplan moved from 1st Ave to Morris’ old location, 1415-19 Westlake Ave. A very interesting street use permit dated June 27, 1930 granted Sam permission “to erect one No. 1072 jeweler’s post clock in accordance with specifications as contained in the catalog of the Joseph Mayer Co.” This is the only reference we have to a Mayer catalog listing street clocks. The clock is a Mayer two dial model with a Howard style base and fancy crested top. It was last seen in 1942. (Fig. 12) Family tradition notes that Morris and Sam were never close. Morris even listed someone in Russia as his closest relative on his World War I draft registration form. Sam, at least, wound and serviced many street clocks around the area. Sam lost his eldest son, Alex an Army Major in the Philippines during the first month of World War II. Sam’s youngest son, Irving went on to become a very well-known Seattle commercial artist and nationally syndicated cartoonist. The ClockSometime in the late 1970’s the clock was electrified, probably by Jerry Martin, a Kirkland (later Port Townsend) street and tower clock restorer. (Fig. 14) This was done by adding a synchronous electric motor to the original Mayer movement frames. The clock lost its small dials and miniature distribution gearing and motion work at the top of the base, probably when it was electrified. Also lost was the Mayer patent electric winding mechanism. Eventually the entire movement and synchronous motor disappeared. The glass windows were replaced by sheet metal panels. Fortunately, the original Vitrolite dials, hands and the complete distribution gearing and motion works were still present in the head of the clock. (Figs. 14 & 17)Other notable features and surprises are described in the photo essay (Fig. 15-29).            15 Chuck Roeser, Essence in Time consultant, holding the remarkably well preserved wooden inner ring to the bezel. It is marked door to indicate it came from the west (sidewalk) facing dial.  Fig. 16 A wooden ring marked “door” to indicate that it goes with the dial facing the sidewalk above the door to the base.  Fig. 17 The bezel, marked “2” to indicate it faces south, down Dexter Ave. with the wooden ring in place.

Acknowledgements First to Rob Ketcherside and

Larry Johnson for involving me in this

project and for their diligent research. To Chuck Roeser for accepting

the consultancy. We had a fun week exploring the King Street Station

and Broadway School clocks before sweating out the removal of the

Dexter Ave. clock. To Ron Edge without whose remarkable photos we could

not have traced the definitive history of the Dexter Ave. clock. To the

very skilled team from Artech that did all the heavy lifting. Mai and

Ansel Ketcherside represented Rob on removal day since he still has to

work for a living. First to Rob Ketcherside and

Larry Johnson for involving me in this

project and for their diligent research. To Chuck Roeser for accepting

the consultancy. We had a fun week exploring the King Street Station

and Broadway School clocks before sweating out the removal of the

Dexter Ave. clock. To Ron Edge without whose remarkable photos we could

not have traced the definitive history of the Dexter Ave. clock. To the

very skilled team from Artech that did all the heavy lifting. Mai and

Ansel Ketcherside represented Rob on removal day since he still has to

work for a living.1Seattle.Gov Historic Preservation Documents. http://www.seattle.gov/Documents/Departments/Neighborhoods/HistoricPreservation/Landmarks/RelatedDocuments/street-clock-designation-nomination.pdf 2Seattle Times, Nov. 26, 1935 3Seattle Times Aug. 8, 1937 4Ibid, Feb. 16, 1938 5Alaska Souvenir Spoons and the Early Curio Trade, June E. Hall, 2004, p. 53 6LeBlanc, Raoul, Joseph Mayer & Brothers Company and E.J. Towle Company Spoon Dies, A Catalog, 1981, West Earth Inc. Seattle 7Metal Arts Group Blog. http://metalartsgroup.blogspot.com/ 8Jewelers Circular, Vo. 85 No. 14, p. 105h 9San Francisco Historic Landmark #77 http://noehill.com/sf/landmarks/sf077.asp 10San Francisco Chronical, Nov. 18, 2000 www.sfgate.com/news/article/Market-St-Clock-to-Tick-Again-Historic-S-F-2695767.php 11The Jewelers Circular, Vol 84, No. 14, May 3, 1922 p. 131 12Joseph Mayer letter to Board of Public Works and Superintendent of Streets and Sewers Seattle street use permit request dated June 25, 1928 13Joseph Mayer letter to Board of Public Works and Superintendent of Streets and Sewers Seattle street use permit request dated March 14, 1928 14City of Seattle Dept. of Streets and Sewers letters Jan. 10, 1924 and July 29, 1927. 15Seattle Times, Aug. 20, 1942 |

|||||||

| Site Copyright: John Runciman © 2000 - 2024 |